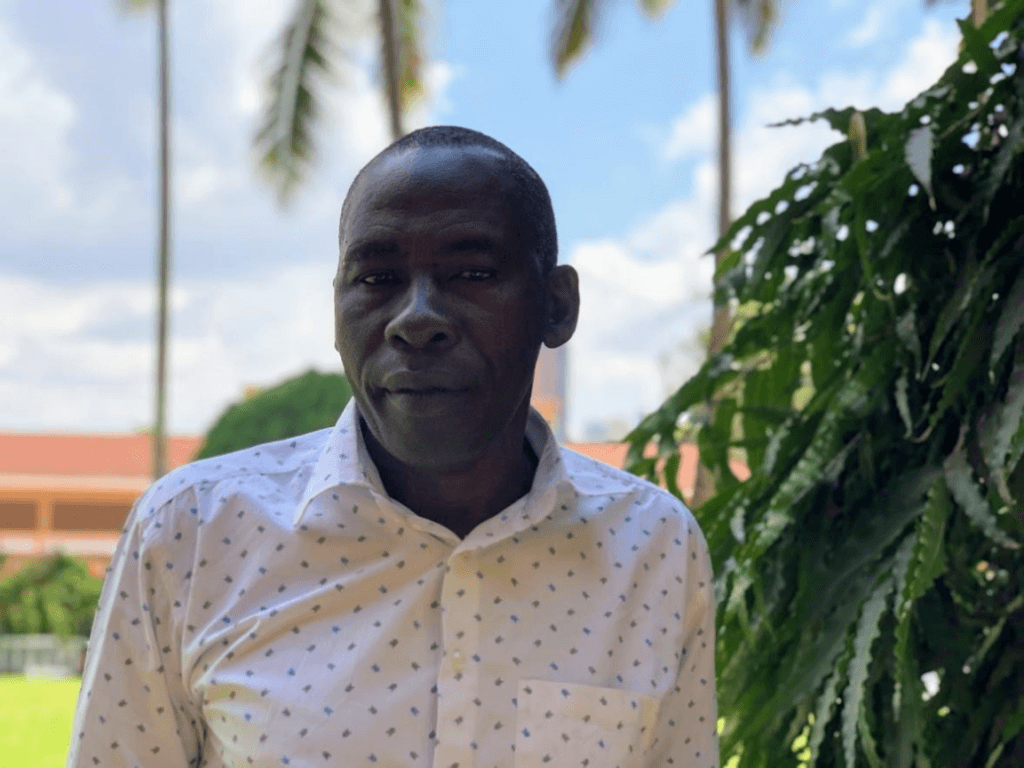

Before the Kagera War in 1979, Kirabira George Kamya, now 61, had qualified to be a primary school teacher in his village in South Eastern Uganda. His dream of becoming a headmaster at his childhood school was one of the

casualties of the war. He worked as a teacher for two years before the ensuing insecurity and displacement changed everything.

Farming was the natural fallback option. Both his parents had been subsistence farmers, and he recalls holding a hoe as soon as he could walk – but their lifelong toil in the farm never lifted them out of poverty. Kirabira says that, at first, he felt that life had forced him to become a farmer. Today, however, he says he is grateful at the turn of events that led him here because of how transformative agriculture has been to his life.

Starting in 2015, Kirabira was part of a group of farmers who played a key role in developing the Nakaseke Maize Standards Ordinance (NMSO). The ordinance is a grassroots-led effort to address the issue of maize grain standards – from maize production to its regional distribution. It sets out bylaws and decrees that ensure maize farmers in Nakaseke produce grain that meets the market requirements embedded in the East African Community (EAC) maize grains standard. This allows Nakaseke farmers to trade their maize internationally and grow their livelihoods and businesses. The ordinance’s development and subsequent enforcement was supported and funded by TradeMark Africa (TMA) through its implementing partner: Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI). It has been heralded as a gold standard ordinance in Africa, and as a model for how local governments across the region can work with rural farmers to facilitate regional trade and help lift them into prosperity.

TMA’s work with SEATINI was implemented in Masindi, Lira and Nakaseke districts of Uganda. Kirabira was one of 700 farmers trained directly by SEATINI to improve their compliance with EAC standards and ensure Uganda maize products compete regionally.

Working with the Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS), SEATINI defined and influenced standards policy on maize and sesame – drafting policy papers and presenting them to the government for adoption. With TMA support, they also established maize and sesame information portals for their trainees and other value chain actors to access easily. These efforts reached an estimated total of 55,000 households in the target districts, including Kirabira.

From a reluctant to a committed farmer

So how did Kirabira go from a reluctant farmer to one of the men leading the charge to improve the production standards for East Africa’s most important food crop?

After the war, Kirabira returned to agriculture by attaining a diploma in organic farming, which saw him recruited by the

National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) as a subcounty procurement officer. In the 90s, his career pivotedto include his teaching skills when he became the founder & chairperson of Gakuwebwa Munno: a farmers’ collective in Nakaseke – the county he moved into after the war. The name translates to ‘advising each other for progress’. Gakuwebwa

Munno unites individual farmers so their collective harvests can trade competitively in local and international markets.

The collective grew but met serious challenges when it first tried to trade its maize internationally. They had contact with the World Food Program (WFP) who were interested in purchasing tons of maize from the collective. This initial excitement quickly turned into tears for the farmers once they learnt that their produce did not meet WFP standards. A potentially life-changing deal had evaporated because their grain was just not good enough. This was a turning point for Kirabira and his fellow farmers, who vowed to get the knowledge they needed to improve the quality of their produce to meet international standards.

Enter TMA and SEATINI: Kirabira says, “I cannot tell you how grateful we were to have found the SEATINI trainings. We thank TMA for funding them. We had just lost the biggest opportunity of our lives, and here was an organisation ready to train us on how to meet international standards so that our farmers don’t lose out again on future opportunities.” These trainings and seminars were the foundation for the Nakaseke Maize Standards Ordinance, and its subsequent replication in Lira and Masindi districts in Uganda.

Today, in accordance with Section 38 of the Local Government Act, Cap 243, Nakaseke district has enacted the ordinance on maize standards titled “Nakaseke District Local Government Maize Ordinance 2015” to develop and regulate the maize industry in the district and ensure the production of quality maize that meets EAC market standards. Kirabira adds, “The Uganda National Bureau of Standards were brought to the table and sensitized us on how to meet the standards so we developed the NMSO. TMA supported all our trainings, seminars and our movement. But it was us, the farmers, that developed the NMSO as we saw there was a need to set bylaws to regulate our produce. TMA’s intervention gave birth to our proudest moment: developing the NMSO.” The ordinance is implemented across two zones in Nakaseke district: the agricultural zone in the south covering four sub-counties including Nakaseke, Kasong’ombe, Semto and Kapeka; together with the cattle zone in the north.

Kirabira is sure to tell you that it is the farmers themselves who have taken ownership of the ordinance’s implementation. Strict bylaws were set out by the farmers then ratified by the local government, all to improve the quality of the maize grain produced in the district. Farmers in the sub-counties covered by the NMSO agree to stringent penalties – like a jail term of up to 8 weeks – for farmers who fail to ensure their produce meets EAC market standards.

Already, district officials from Lira and Masindi have come to Nakaseke to learn from Gakuwebwa Munno’s efforts and, with help from TMA, have developed their own ordinances.

Expanding quality grain farming further

Today the collective has over 1000 farmers, and all of them strictly adhere to the NMSO. Energised by their increased regional trade volumes now that their grain meets EAC market standards, the farmers collective’s dreams have also grown. They want to add 40,000 farmers from adjoining districts to the collective and own 300 acres for commercial maize farming thereby taking advantage of economies of scale and trade internationally at truly competitive prices. They also want to own a maize milling factory so the farmers themselves control more parts of the maize value chain.

“These are not dreams we could even mention before TMA’s interventions. The trainings showed us what’s possible and now, with the ordinance in place, the quality of our grain has given us a voice at the table where decisions are made,” says Kirabira.

Kirabira says his dreams of becoming an educator have been met in a round about way: with his involvement in training other farmers on maize grain standards, and even being consulted as a researcher for the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO): “These trainings have had a huge impact on us. For example, big clients used to complain about the moisture content of our grain. We didn’t even know what that meant! SEATINI and TMA sensitized us and connected us to policy makers so our voices are heard. We learned and we train others,” he says.

One by one, rural farmers in Nakaseke are lifting themselves out of poverty into self-reliance. Kirabira has all but forgotten the war that brought him to Nakaseke, and challenges him and fellow farmers faced before the trainings and the NMSO:

“Before, middlemen would frustrate us and determine the prices they would buy from us. Now our maize is an international quality grain. We get to decide how much we’re selling the maize for. We get to decide our livelihoods!