That’s the main conclusion from a new report Africa’s Development Dynamics Achieving Productive Transformation, published by the African Union (AU) and the OECD on November 5.

As it stands, productive transformation is not taking off, especially in the employment-intensive sectors where it is most needed, the report finds. Far from catching up, Africa is falling further behind emerging markets in Asia.

The Africa-to-Asia labour productivity ratio has decreased from 67% in 2000 to 50% today, the report finds. African exports of consumption goods to African markets decreased between 2009 and 2016, both in dollar terms and relative to the continent’s GDP.

- “Without a strong and co-ordinated policy push,” the report says, “African firms risk losing out to new global competitors.”

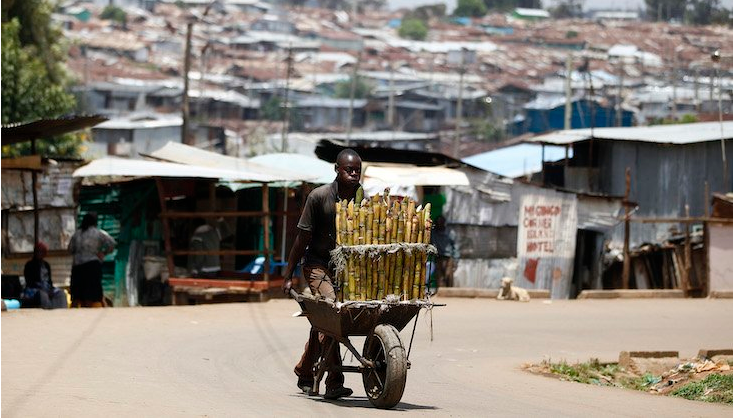

About 42% of Africa’s working youth live on less than $1.90 a day and only 12% of Africa’s working-age women were in waged employment in 2016, according to the report.

- The number of people on that income level increased by 31 million between 1999 and 2015 to 407 million.

- In some countries, almost 91% of the non-agricultural labour force remain in informal employment.

The annual total of 29 million new entrants to Africa’s labour markets risks becoming a cumulative addition to the jobless total. If jobs for them are not found in one year, they will need to be created the next year.

Clusters key

Many entrepreneurs lack basic capabilities, the report finds.

- Most youth entrepreneurs in Côte d’Ivoire and Madagascar lack skills in areas such as bookkeeping, multi-year planning and human resources.

The AU and the OECD identify three key priorities: developing business clusters, fostering regional production networks, and improving the ability of exporters to compete.

African countries are becoming more successful at building clusters, which enable governments to make the most of their assets by investing in areas which have concentrations of knowledge and skills.

- Some previous special economic zones in Central Africa and West Africa are described as “cathedrals in the desert” which were located in remote areas without the necessary supporting conditions.

- The report gives the examples of Tangier-Med in Morocco, the Eastern Industry Zone and the Hawassa Industrial Park in Ethiopia, and the Kigali Special Economic Zone (KSEZ) in Rwanda as clusters that have succeeded in attracting multinationals.

- Firms moving into the KSEZ have seen major increases in sales and numbers of permanent employees, the report says.

Yet African firms are too often cut off from each other, preventing the spread of new technologies and know-how. Kenya, for example, is relatively weak in such linkages, the report finds.

Capabilities remain confined to the most productive firms: Ghana’s top 1% most productive firms produce on average 169 times more value-added than the other 99%.

The weakness of regional sourcing is also cause for concern.

- The average level of regional sourcing in Africa remains under 15%, compared with more than 80% of exports in industries such as motor vehicles, textiles, computers, electronics and optical products in Southeast Asia.

Removing non-tariff barriers may be five times more effective than getting rid of tariffs, the report says.

- Exporters need simpler administrative procedures and better infrastructure, especially flights, roads and ports.

- Companies need to do more to meet quality standards: Malaysian firms alone filed as many International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certifications as all African firms in 2015.

Bottom Line: Coordinated policy actions on clusters, regional sourcing and non-tariff barriers are urgently needed to avert further increases in the numbers of Africans living on less than $1.90 a day.