Villagers in Ruziba say the old government Health Centre was “precarious.” Photographs of it suggest stronger adjectives, such as ramshackle, tumbledown or dilapidated.

The new Health Centre is far from precarious. It is smart, solid and a source of local pride. And it was built on the foundations of a revolution sweeping Burundi – tax payments.

“It was built with our tax returns,” says Dr Bellejoie Louise Iriwacu. “I am very, very proud of it.”

The Rubiza Health centre, and dozens like it, was funded by a streamlined tax-gathering system adopted by the government to maximize revenue in an economy that sits near the bottom of the world’s least-developed.

When she qualified as a doctor a year ago and got hired by the government, one of her first acts was to go to the Office Burundais de Recettes (OBR) – the country’s tax-collection authority – to register to pay tax on her modest salary.

OBR was created in 2009 with assistance from the British government’s DFID aid wing and then through an organization called TradeMark Africa (TMA), which is helping East African Community (EAC) states modernize and integrate their economic infrastructure.

The EAC groups Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi and is home to 160 million people.

Some young workers might have baulked at making a system to deduct tax from their salary a priority as they began a new life and a new career.

Not Dr. Iriwacu. “Not paying taxes means no money to make the country live, to help it expand, to help it breathe,” she says, taking ten minutes off from treating a steady stream of patients at the centre.

“As Burundians, we have to pay tax. It’s our duty. If someone just gives you something for nothing that is meaningless. But if you help pay for something, and then you are part of it. You are a part owner.”

As a taxpayer the young doctor is part owner of a centre a half-hour drive from the capital, Bujumbura, that looks after hundreds of people every week and offers services from maternity care to vaccinations.

Not that Burundians didn’t pay tax in the past. Some did, some didn’t, but the tax collection system was so riddled with loopholes that the government’s lifeblood funding was – “precarious,” – the word used by Eugene Mujambere, Director of Infrastructure and Equipment at the Ministry of Health.

“OBR has given us the means and now we are putting that tax money to work. We’ve built around 40 Health Centres with government revenue from taxation” The headquarters of the revolution is a modest three-storey building in central Bujumbura where dozens of staff in smart blue uniforms sit behind the computers that have thrown the tax net over the country.

“Tax revenue has doubled since OBR was set up,” says Kieran Holmes, the OBR Commissioner General. “We currently have a delegation here from Togo right now looking at how we did it. We’re the first francophone country to set up a system like this, and other countries in West Africa envy us.”

In the past the tax payment was something of a lottery with individuals and businesses striking private and corrupt deals with the customs authorities and tax offices.

“We swept it all away and put it all under one roof. We brought everything together, linked it all with I.T. and cut out the corruption,” says Holmes.

“Along the way we have created a level playing field for businesses so that investors are interested in coming in now. They know that all enterprises pay tax and that no -one has an unfair advantage. It’s created a much more attractive business environment. ”

In the past year Burundi has also been named one of the top 10 reforming countries in the world by Ease of Doing Business organization. Once an individual or business is in the OBR system, he, she or it becomes a reliable source of revenue on which the government can make its plans to climb out of the league of Least Developed Countries. It is currently 185th out of 187 in that survey.

“The whole point of this exercise is that the government is empowered because it now has additional revenue to finance its plans,” says Holmes.

The government does have plans too. They are, donors say, neither grandiose nor over-ambitious. All are based on the certainty that there will be cash in the government kitty to pay for them.

One is a hydroelectric dam at Mpanda that will cost around $40 million. “We need power to transform this country. We need education and health services too, and you can’t have either without power,” says Pierre Barampanze, advisor at the Ministry of Energy.

Another is a major hospital at Karuzi, which will eliminate the need for Burundians to travel to Kenya or further afield if they need complex medical interventions or specialist treatment.

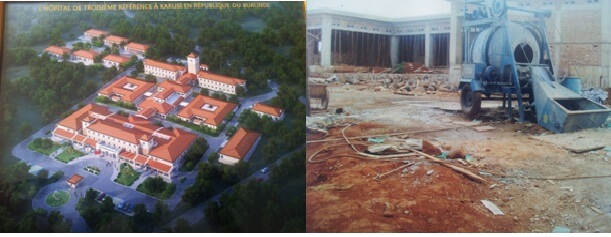

An artistic impression of the new Karuzi Hospital and current on-going constructions

The hospital will cost in the order of 21 billion Burundian francs and be built entirely from tax revenue. Construction started in August 2011 and is supposed to end in February 2013. It will have 150 beds offering 13 services for Karuzi province and the surrounding areas.

“What has happened here is really quite remarkable,” says Gabriel Toyi, head of cabinet in the office of the second Vice-President.

“There was so much fraud and cheating going on in the tax areas, as much in customs duties as in tax returns, but now revenue has gone up by nearly 40% in a year,” he says.

“We are modernising. Everyone can see it. Everyone has a stake in it. But it is the tax money that is helping us live.”