‘The gateway to East and Central Africa’ and ‘the regional hub of international trade’ is how the Kenya Ports Authority website proudly introduces the port of Mombasa on Kenya’s coast. It goes on to declare that the port is ‘Growing business, enriching lives’ – a commendable role which should have equally laudable consequences for the people of East Africa as successful trade translates into reduced poverty.

Yet it wasn’t always so. While the port has been the gateway to East Africa for the last 100 years, there were times when business in the region was obstructed due to congestion and delays at the port that resulted in overdue consignments, often of raw materials needed for manufacturing. Anthony Weru, Senior Programmes Officer of the Kenya Alliance of Private Sector Associations (KEPSA) recalls December 2012. “Some of our members had to lay off staff”, he said, “Because there were no raw materials to process. They were all at the port.”

Only 18 months later Weru is telling a different story. “For the last six months we have seen a tremendous change and improvement in efficiency at the port due to political will,” he said. “Cargo clearance, either to or fro, is now taking an average of four days to its destination (in Kenya) when it used to take 14.”

All depends on port efficiency.

For the private sector, which in Kenya consists of up to 90% of the work force, the ability to forecast when raw goods will arrive makes all the difference to wealth creation. Yet it all depends on the efficiency of the port system, combined with a transport infrastructure that is fast and reliable. Thus, the role of the Mombasa port in this process is paramount.

The port is run by the Kenya Ports Authority (KPA) and is often held responsible for delays in both imports and exports, despite many other agencies being involved in the process, including the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (Kephis) and the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS), to name a few. If just one of the agencies acts slowly or inefficiently, then the whole process is held up to the detriment of the importer or exporter.

In the past, a small business could go underbecause of the actions of one tardy agency, with the inevitable consequences of unemployment, lack of competition and higher prices. Today there is a collective determination to get it right, so that East Africa can profit from new improved efficiency, in turn creating a competitive business environment that will attract investors, increase trade and ultimately reduce poverty. This is especially so when estimates are that the amount of cargo passing through Mombasa Port will, by 2030, increase almost six fold, to 117 million tonnes, from 20 million tonnes in 2011.

Shared aspirations

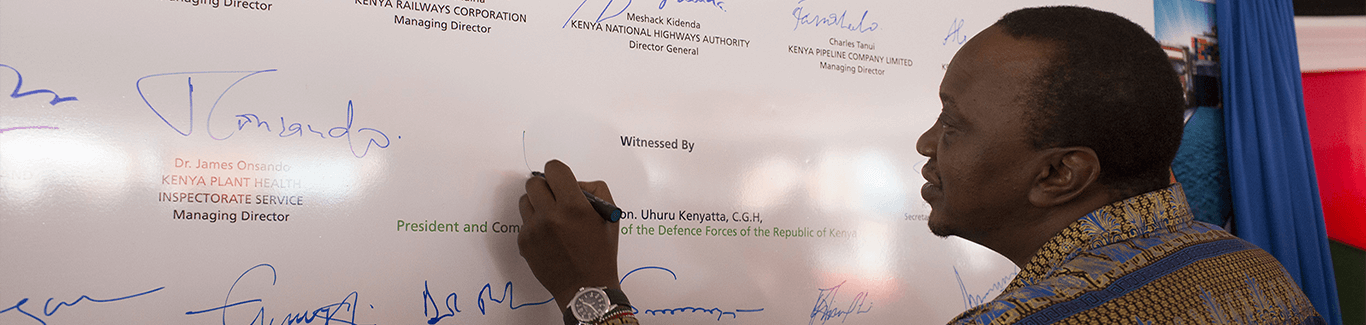

The new, shared resolve is embodied in the ‘Mombasa Port Community Charter’, which “Proclaims the desire of the Mombasa Port Community to realise the full trade potential of the Mombasa Port Corridor”.Driven by a strong political will which comes from the very top, the Charter represents the culmination of stakeholder consultations, including government agencies, the business sector, civil society, the port community and special interest groups. Signed by 25 different agencies it commits to overcoming obstacles and reaching, maintaining or exceeding standards that will deliver goods to the market with maximum efficiency and minimum time.

TradeMark Africa (TMA) is one of the signatories, having invested US$53 million in the port corridor rehabilitation to strengthen infrastructure, improve productivity and create an enabling institutional framework. TradeMark Africa (TMA) also played a large role in the creation of the Charter. TradeMark Africa (TMA) Kenya Director, Chris Kiptoo, is optimistic. “The document is a declaration of intent”, he said, “To commit certain actions which, when combined, will create a seamless corridor from the port through the northern corridor, which will in turn increase the efficiency and competitiveness of trade in Kenya.”

Monitoring commitments

Good intentions are one thing, actions another. How can people be sure that all parties are following up on their commitments? Kiptoo explained that key performance indicators will be measured on a live dashboard – an IT system that captures live data and transmits it online – known as the Northern Corridor Performance Dashboard. Such things as ship waiting time, vessel turnaround time, and cargo dwell time, will all be available for anyone to see. In addition, a new single window system, operated by the Kenya Trade Network Agency (KenTrade) whereby all import/export documentation will not only be computerised, but can be accessed by all parties, will mean that any agency holding up the process can easily be identified. As a last resort, said Kiptoo, there will be peer pressure and sanctions to ensure that all agencies honour their commitments.

The KPA is enthusiastic about the progress it has already made towards its vision of becoming a world-class seaport. Acting Head of Development, Farouk Mohammed, a long-term employee at the KPA, is visibly proud of the port’s achievements so far. “In the last three years we have seen a lot of changes,” he said. “Before we used to clear cargo in anything from 15 to 24 days. Today we are talking about 3.9 days – this means that a container is cleared within a day.” In addition, he noted that they have cut 10 days off the time it takes to get cargo from Mombasa to the Malaba border with Uganda, down from 19 days to only seven or eight.

“Our business is not to keep cargo here,” said Edward Kamau, Acting Head of Corporate Development at the KPA. “The advantage of the Charter is that it is going to bring big commitment. People are aware of this commitment and will sign against their obligations. Therefore accountability becomes paramount.”

The Charter enhances the business climate

The Shippers Council of East Africa (SCEA), which represents cargo owners, also welcomes the Charter and the accompanying dashboard. “The key is competitiveness and efficiency,” said Ageyo Ogambi of the SCEA. “Efficiency is good for the Kenyan economy because investors can see a good investment opportunity. More investors have a spillover effect. The consumer will benefit in terms of better pricing and maybe better quality as there will be more money for logistics and production. Removing bottlenecks means transport costs will come down. Better turnaround time means better use of resources. But most important is that the cost benefit can be passed on to the consumer. Port efficiency,” he concluded, “has the possibility to enhance the competitiveness of the general business climate and the economic growth of the region.”