The first Electronic Single Window (eSW) was introduced in Singapore in the late 1980’s. The Singapore TradeNet links multiple parties involved in external trade, including 34 government agencies, to a single point of transaction for most trade related transaction such as Customs clearance and payment of duties and taxes, processing of export and import permits and certificates of origin and collecting trade statistics. Between 1989 and the maturation of the system in the early 2000’s the major achievements included:

- Processing time was reduced from 2-7 days to within 2 minutes.

- Number of documents required fell from 3,035 (depending on the transactions) to 1.

- During this period the number of daily transactions processed rose from 10,000 per day to 30,000 per day.

- Freight forwarders estimate that they save 20-35 per cent of the cost of handling trade documentation.

- Payments of customs duties enter government coffers much faster than before.

- The compilation of trade statistics is substantially improved, benefiting the trading community as well as national authorities responsible for trade policy and economic surveillance.

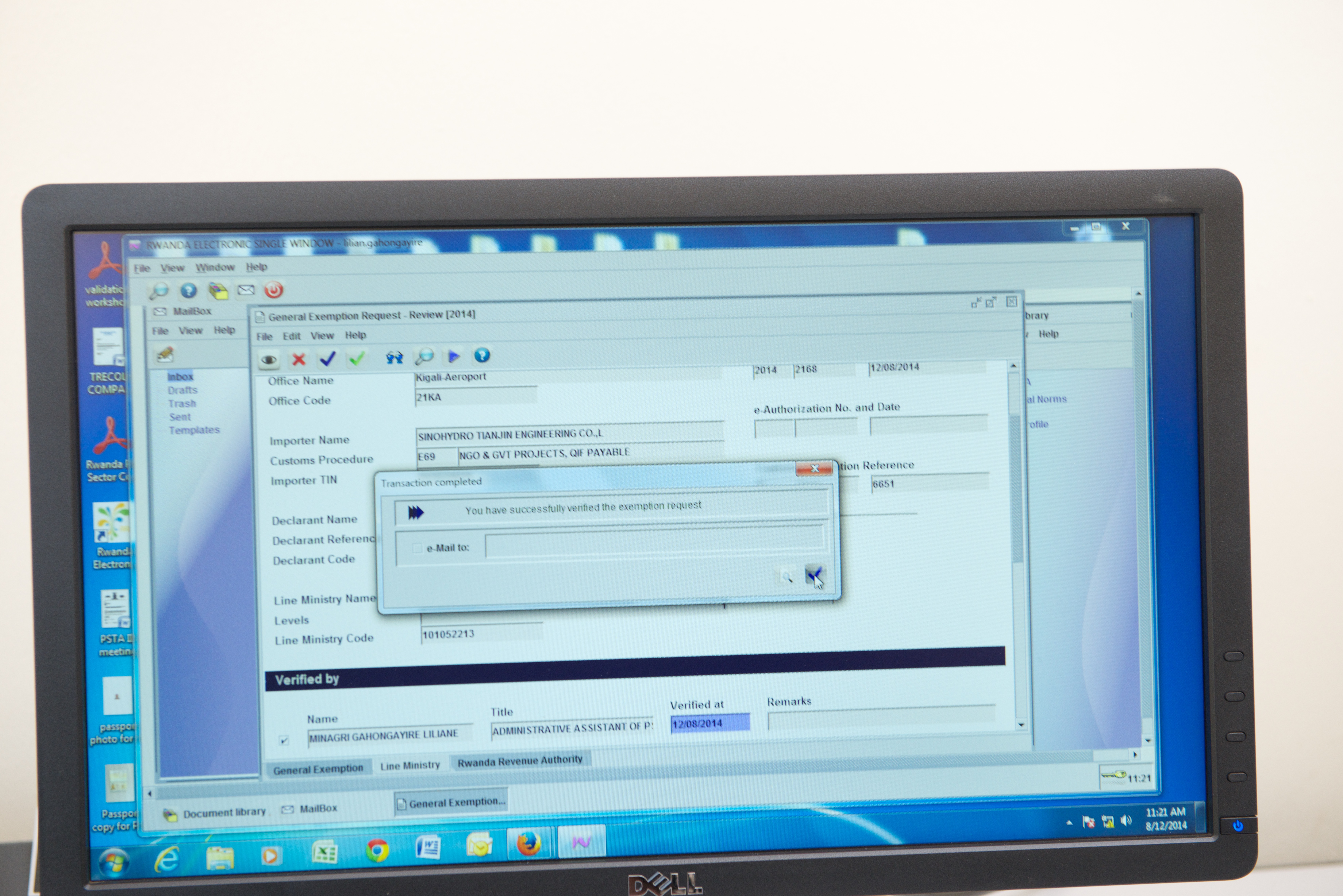

Since the launch of the Singapore TradeNet, over seventy countries have established eSWs of varying complexities, including over half a dozen or so in Africa, including the Rwanda eSW launched in 2012.24 This case study provides a brief overview of two different business models for implementation of the eSW and examines key pros and cons of the two models to inform

TMA and policymakers in the region who may be considering establishing eSWs. This is particularly relevant given all TMA countries are members of the WTO, and will need to implement the Trade Facilitation Agreement, which urges countries to establish or maintain eSWs.

The public model

The government funded and managed eSW is the model adopted by the majority of countries, including Rwanda and Singapore. The national customs authority is the implementer and takes on the coordination responsibility within the government. Governance is mostly guided by a Committee that represents Ministries involved in trade and trade oversight, private sector stakeholders selected from Members of the Chamber of Commerce. Leadership of this Committee tends to be entrusted to the Ministry of Finance.

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

Low charges for clearing agents and traders (e.g. approx. $4 per declaration in the ReSW case);

|

Mobilizing the necessary financing may delay or prevent the start of the project;

|

The PPP model

Under the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model, the eSW is set up and managed by a private company funded by a combination of public and private funds. This is the operational model for Ghana, Mauritius, Hong Kong, Senegal and Mozambique.

The share of private contribution in the total equity varies according to local circumstances. In practice several of the PPPs that operates ESWs have a majority of private funding. One good example to date of this business model is GCNet in Ghana. GCNet was created in 2000 with equity of $5.3 million, with 60 per cent contributed by a Swiss company Societe Generale de Surveillance (SGS), 20 per cent by the Ghana Customs Authority, 10 per cent by the Ghana Shipping Council and the remaining 10 per cent by two local banks. To ensure the smooth launch and continued operation of the GCNet, SGS infused another $1.7 million in 2014.25

The Government of Ghana selected this approach to ensure an experienced implementing agency at the helm of the eSW. The Customs Division of the Ghanaian Revenue Authority (GRA), who would have been the logical implementer of the eSW from the government side, was at that time not considered to be in a position to lead the new project and to ensure the adherence of OGA to the project.

GCNet, following Mauritius’ example and later followed by Mozambique, selected to adapt the Crimson Logic’s IT platform to the Ghana environment, thereby avoiding the need to spend scarce further resources on the development and installation of a brand-new IT platform. According to an independent evaluation of the GCNet, the PPP was successful in Ghana, despite the relatively high costs of the project and was the basis for the renewal of the contract.

Moreover, the international expertise facilitated the broader customs modernisations initiatives, and helped to provide advise on issues such as streamline transit procedures and introducing truck tracking systems.

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

|